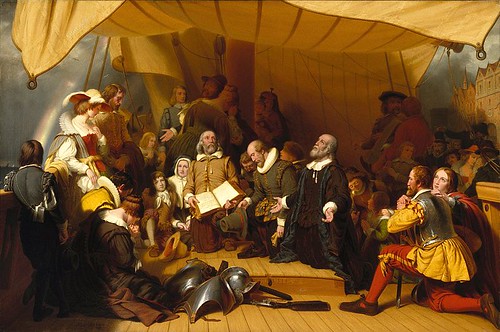

John Parkson drove the tip of his boot into the wooden floor beneath

him, amusing himself as he watched the rotting wood dissolve into a fine

dust that coated his foot. A heavy scent of mildew and an overwhelming

humidity were the daily troubles of his job as a boatman on the

riverways of Virginia, a thankless task that paid just enough to get him

by. Still, he didn't do the job so much for the money as much as for

the freedom. His daily journeys, back and forth along varying trading

and travel posts, allowed him the chance to see the world in a way few

of his fellow former colonials could. He considered himself a learned

man, in a way that the educated of the world might not expect. After

all, the traveling he did gave him a chance to run into all sorts of

people. He might have been born into the backwoods of the state, but his

traveling exposed him to all sorts of philosophy and propaganda. Every

day he heard the rhetoric that echoed of the Revolution, about how all

men were created equal and each man had a chance for success in this new

country of theirs. Still, all that took on a different perspective the

day he began to work with Elwood Hargrove, a black boatman employed by

his owner to work the riverways and earn some extra income for their

plantation.

*****

He hadn't heard the quote, but Juan Martinez knew, vaguely, what had been said. It had been parroted on a few news channels over the past few weeks, and the gist of it was that one of the Republican candidates had suggested building an electric fence along the border with Mexico. Juan didn't consider himself very political, and the truth was that he supported a restriction on immigration. His own family had come from Mexico two generations before, but they'd always been in support of legal immigration. They somewhat resented the waves of illegal immigrants that came to the United States and avoided the same tasks their grandmother, matriarch of the family, had endured to gain citizenship. All the same, life was sacred, and you didn't joke about killing immigrants. He wondered if these politicians knew just how harsh life was for illegals trying to cross over, about the rape women endured and the men who got killed moving across the border. Life wasn't easy if you were coming over illegally, and joking about their deaths was silly, given the reality of how harsh their lives were.

His family had always voted Republican but, given the candidates that he was faced with, Juan was increasingly finding it difficult to support anybody on the conservative side. Every time he heard Mexicans talked about like animals, like they were dogs that needed to be trained properly, he was disgusted. It just wasn't right that his people were treated so badly.

*****

Joseph Martin sighed, listening to the comments coming over the television. There had been a debate the other night, and the Republicans had been talking about welfare and Medicare. Martin had an invested interest in the discussion. He was the son of a contractor and had gone into the same work himself, spending most of his life working on houses, working on floors and walls. It wasn't easy work, but it was what he loved, what his father had shown him to do. There were downsides to the work, though.

First of all, never in his life had Martin had adequate healthcare. He'd spent a lifetime avoiding going to the doctor, waiting out pains he'd feel in his back or arms, buying whatever generic medicine he could afford whenever he'd gotten sick. He'd spent even less time at the dentist than he had at the doctor over his thirty years, and while he'd gotten along well enough, he'd always worried what would happen if something catastrophic happened to him or his family. He and his wife had just had a child, and every day he prayed the baby would be healthy and happy. Church members contributed to taking care of it when he and his wife worked the same days, she at her job waiting tables at a local diner, while he tiled or did roofwork.

The biggest problem, though, was that the housing market had gone into collapse, and had only slowly been recovering. Every time he heard these candidates talking about makers versus takers, he couldn't help but think, <em>I am a maker.</em> He was, he helped make houses. Somehow, though, he didn't think that the Republicans were thinking about him when they got into these sorts of debates.

*****

Jackie McMahon shook her head as she listened to the podcast airing over computer's speakers, sitting in her office on the top floor of a corporate tower where her office was located. She'd spent an entire morning dealing with her hair, which had always been too thick and unruly for its own good and required a combination of chemical agents to straighten, a process she'd never been happy with but had been forced to acknowledge as necessary. Her mother had always been an advocate for letting her hair grow out naturally, but Jackie preferred a straight, sleek look as opposed to the thick bush of hair it could become if she let it come out the way nature intended.

It was a difference of generations. Her mother had been an activist in the 70s, at the same time an advocate for Black Pride as well as feminism. Jackie wasn't nearly as extreme but like most African Americans, she shuddered when she heard the way black Americans were discussed. It didn't take much searching on twitter to see references to Obama as the "N" word, and one time, during a trip to a small town in Texas to visit her grandmother, she'd overheard a few men at the local gas station refer to him as a monkey.

She wondered if they knew she could have probably bought that gas station outright. She'd spent a lot of time building the capital and finances to strike out on her own as a financial manager, and from her Dallas office she dealt with influential clientele that brought her significant economic gains. In theory, she might have made the perfect Republican, someone with income about 250,000 who would probably like to avoid being taxed. Still, every time she heard her people referred to as lazy, or takers, or animals, she shuddered. Just as importantly, she remembered what it was to struggle. Yeah, race was an issue, but there were a lot of people out there struggling. They didn't just have black skin. They were Asian, hispanic, white, and every other sort of ethnicity under the sun. Nobody had an exclusive claim to poverty.

*****

Elwood Hargrove chuckled slightly, looking out over the river that wound its way past their trade station. From here they unloaded the ferries and moved the goods into town, where merchants would sell it off for profit. "It's one of my favorite things about this job," he explained to John Parkson, his hands tucking into his pockets. "You see, plantation work is hard, but I'd work it just as hard as any other man. Except, my soul likes to fly. It's like a bird, you know? I can't live without the feeling of being on the go."

John Parkson smiled, looking over at the young negro, a man no older than himself. "Funny you say that. I'm the same way, actually. I've never felt it was a good thing for a man to be tied down too much."

"I hear that. You know, it's like I've always said. My body might be a slave to somebody else, but there's nobody that can make a slave of my mind. Getting up and down these rivers, I see and hear so many things that other people could never imagine. Everyone talks about the Revolution well, I get to read it. I get to listen to it. You know we had some Frenchmen here at the post not too long ago, you remember them?"

"Yeah, I do actually. Funny accents, I was a little surprised they even spoke English."

"Oh, French people speak it. Important for making money, same as English people have to learn French. You know Thomas Jefferson, he loved spending time in France."

"I heard about that. I hear he spends a lot of time over there."

"Yeah, French have the same ideas about freedom that America does. At least it sounds that way. Those Frenchmen, they were asking how I could live in a country that claims all men are born equal, and yet be a slave. I didn't really have much of an answer for that."

John sighed, eyes floating downriver to the horizon. "Nobody's equal, much as we'd like to talk about it. You know, you might be a slave, but I figure we probably take home about the same amount of money. You might have to give your money to your master, but I've got to give mine to the taxman."

Elwood smiled. "That's a damn shame. We really are equal, just not in the way you might hope for."

*****

When Juan Martinez went to the booth to vote, he had a decision to make. Vote the way his family had always voted, or vote Democrat. It did really bother him to no end that Mexicans were disparaged relentlessly in the Republican debates, but in the end, as he stood there, another factor came into play. His hand slid into his pocket, fingers wrapping around a few loose coins there. Juan considered himself a decent man. A mid level human resources manager at a telephone company, he thoroughly enjoyed the work he did. He never thought he'd be rich, but he'd always imagined that, as a part of the middle class, he'd be able to provide adequately for his family. He dreamed of sending any future child he might have onto a good college, and give them the opportunities he'd never had. Maybe the fourth generation of Martinez kids would be the ones that struck gold for the family.

College was getting expensive though, and he kept hearing Mitt Romney's voice in his head, when he'd told one girl that the best solution to keeping college costs down was to shop around. Another time, he'd suggested borrowing money from parents in order to start up a business. Martinez laughed, a quiet laugh to respect the voters in the booths next to him, but a laugh nonetheless. He'd never be able to loan tens of thousands of dollars to any child he might have, and all colleges were getting increasingly expensive these days. Even community colleges were raising rates, so he wasn't sure what good shopping around would do. He didn't want his children going into heavy debt just to get an education.

So, as he looked at the ballot in front of him, he did something his parents probably never would have imagined doing themselves. He punched Democrat. He stepped out into the cool air, eyes flickering out to the mountains that hovered around Denver. He certainly had no regrets about his decision.

*****

Joseph Martin stood in line at the local polling station, shocked by the huge turnout. He'd arrived at ten that morning because, quite frankly, he'd been unable to find work that week. So here he was, in line, waiting to vote. As he thought on all the problems his family was facing, he just couldn't imagine voting Republican. Obamacare promised a chance to get some decent healthcare. Republicans had been talking about repealing and replacing, but they'd never given any details about what they'd replace the program with. Mitt Romney had said that the United States gave adequate medical care because you could use an emergency room. Martin wasn't sure he understood what poor medical coverage that made, or how that caused medical costs to skyrocket.

At least Obamacare expanded the coverage and allowed for exchanges where he could, hopefully, find something to help his family. As medical care currently existed, he had no chance to afford a medical plan. So, eyes locked on the doors that were still at least an hour away, he tucked himself into his jacket, lowering the 76ers cap he had lower onto his head and sealing his hands into his pockets. He wasn't voting for a handout, here. He was voting for some help for his family.

*****

Jackie McMahon decided to watch election night at an office party she had sponsored. Her boyfriend, a young Asian tailor who made a living fashioning shirts and suits, was scheduled to arrive soon. She was hoping sooner than later. As she watched the election results at about nine that night, it was already looking bad for Romney. Yeah, he was ahead in the electoral votes in a few states, but non of the predictive polling looked like he was going to grab many of the swing states.

She'd voted early. She could afford to, given her status and position. It was unfortunate that the Republicans had gone to such length to try and restrict early voting. You know who that affected most? The poor, students, minorities. At one point or another, her mother had been all of those. Jackie hadn't had it as bad, but she'd still know poverty. Her college education, something her mother had saved and struggled to buy for her, had been the key to Jackie's success. If she decided to have children, they wouldn't have to worry about going to a good school. Still, she couldn't in good conscience vote for people that had made voting a struggle. Her own family came from a background of people that had fought for the right to vote, and to find equality. Jackie wanted to pass that along.

*****

As John Parkson and Elwood Hargrove sat on the pier, watching the sun drop in the distance, they silently acknowledged they'd be doing no business that day. The boats had been slow in coming, so soon, they'd be retiring to the beds they kept in the trading station.

"Never thought I'd be sharing room with a white man, to be honest," Elwood said, hands crossed in front of him. "Of course, that's natural, considering where I come from."

"Guess it's the same for me. I didn't ever think about it, but I can't say it bothers me, to be honest. We're both in the same boat." He chuckled, reflecting on the pun. "Yeah, you and me Elwood, we've both got some of the same problems. Can't say I envy what you go through though."

"Hey you know, it is what it is. I've got it better than some, and some have got it better than others. You might have it better than me, but we're both struggling just to make ends meet. Seems like we're both equal in that regard."

"Yeah you know, they might say all men are created equal, but you have to find where you're equal. You have to work for someone else. I don't, but if I don't, I'm not going to survive long. Not sure how much of a choice that is."

Elwood sighed, leaning back, hands resting on the rough surface of the dock. He looked far into the distance, onto the dimming skies. "Not sure what this country's going to look like in a hundred years. Even if all the races were equal, people still wouldn't be. It's a class thing, not a race thing. Men talk a good game about how we're all equal, but there's always going to be one group of them that wants to rule over the other, doesn't matter if it's a slave or a worker. So people like you and me, we've got to stick together."

John Parkson shook his head, clambering up onto his feet. "It's getting late. I know you have to be as hungry as I am, unless you've been sneaking food while I haven't been looking."

Elwood turned slightly, looking up at his friend. "If you're offering to make a meal, I think I'll accept."